Paycheck

He wondered about it sometimes, wondered where it had gone

but never asked. It seemed kind of—what—rude? Pushy? Ungrateful? Whatever, the

bottom line is that while he wanted to know, he never asked.

It wasn't like he obsessed over it and months would go by without him giving it

a thought but then something would set his mind working in that direction and

he'd wonder about it all over again.

His money, that's what he wondered about. His money.

It wasn't like he needed it, what with Bruce picking up every expense but he

still wanted to know what happened to it. Besides, it bothered him that he was

living off the Wayne fortune—it wasn't like he was destitute or anything and

some part of him rebelled against the idea that he was living on charity. No, of

course Bruce or Alfred didn't feel that way; in fact, he knew better.

When he was about ten or eleven it occurred to him one day that he wasn't a

Wayne, he was a Wayne ward—sort of like ward of the state if you lived in the

State of Wayne, which he did. Not long after that he saw an old Saturday Night

Live clip about Wayne's World and he decided that he lived in Wayne's World, in

the State of Wayne. It made him laugh, though he never told anyone what he

thought was funny.

He wasn't living there because of pity or charity or any of that, he knew that

and pretty much had since the day he first walked through the front door. Well,

that wasn't completely true; he'd known it after he'd arrested the man who'd

killed his parents and Bruce let him stay, assumed that was where he'd live and

made him Robin. That wasn't pity, that was a whole `nother statement and it

changed his life.

He knew they'd both be upset and insulted if he brought it up, but it as still

there in the back of his brain. He wasn't a charity case, he could make his own

money and pay his own way—he'd done it for years and it bothered him that he was

freeloading.

Okay, he took that back; he wasn't freeloading. He worked, he was Robin, he kept

his grades up and went to every society thing he was told to be at. He did his

job as well as he could.

And he knew Bruce loved him and was happy to have him there, but it still didn't

completely sit right. His father, his real father had been proud, never took

anything from anyone and had ingrained the idea into him from the time he could

understand. You took care of yourself, you took care of your own and you never

let yourself become dependant because then you weren't your own person.

He'd worked for years, since he was three years old and he knew that he was paid

for those years and all those routines he'd done with his parents, all those

tours, all those special performances. They weren't freebies or a hobby, they

were their livelihood and the Flying Graysons were the headliners of a

successful circus—they were draws, they brought in the crowds and they were paid

for their time, their talent and their nightly risk taking.

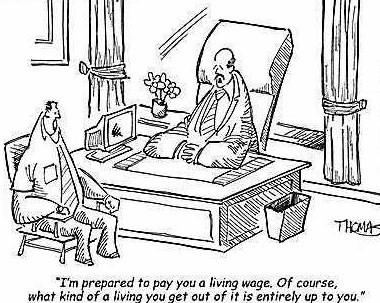

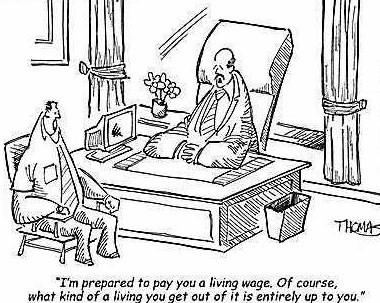

And, since he was a minor, he knew that at least fifteen percent of his own pay

was put into an iron clad, unbreakable trust, held until he was a legal adult.

His parents had to. It was the law, the `Coogan Law'. The Coogan Law was named

for famous child actor Jackie Coogan. Coogan was discovered in 1919 by Charlie

Chaplin and soon after cast in the comedian's famous film, The Kid. Jackie-mania

was in full force during the 1920s, spawning a wave of merchandise dedicated to

his image. It wasn't until his 21st birthday after the death of his father and

the dwindling of his film career that Jackie realized he was left with none of

the earnings he had work so hard for as a child. Under California law at the

time, the earnings of the minor belonged solely to the parent.

Coogan eventually sued his mother and former manager for his earnings. As a

result, in 1939, the Coogan Law was put into effect, presumably to protect

future young actors from finding themselves in the same terrible situation that

Jackie Coogan was left in.*

So—where was it, his money, where did it end up?

That was where things pretty much stood for years. Dick privately wondered about

it while doing his level best to live up to what Bruce expected of him. It was

status quo.

Until…

C'mon, you knew that wouldn't be the end of the story, didn't you?

He was twenty-one, had dropped out of Hudson, lasted one semester at Gotham U,

bummed around for a while and now was in training at the Bludhaven Police

Academy against Bruce's vocal better judgement. It was Friday afternoon and he

was short of cash, there was an `out of order' sign on the ATM so he had to

actually go inside and deal with a teller.

Friday. There was a line, one of those lines where you have to go through the

velvet rope maze until someone finally calls `next' so you can do your thing. He

finally handed over the withdrawal slip, wanting to get his two hundred dollars

and be on his way.

The bored teller typed his account number into the computer without looking at

him, gave the screen a cursory glance and counted out ten twenties, counted them

again, put them in an envelope with his receipt and handed them over.

That was all he wanted but while he was there, oh, what the hell…"Could you give

me a balance for that account?"

"Sure."

The teller looked at the screen, looked again and raised his eyes to really look

at the guy standing in front of him. He was good looking in a vaguely ethnic but

incredibly handsome kind of way, shortish black hair, good build without being

overdone, casually dressed in a worn leather jacket, jeans and a white tee,

holding a motorcycle helmet under his arm. And the jacket looked actually worn,

as opposed to distressed by Ralph Lauren or somebody. Authentic. Interesting.

"Problem?" So the guy didn't feel like being cruised; damn.

"Uh-no. No, `sorry." He wrote a number on a slip of paper and handed it across

the counter. "Your balance, Mr. Grayson."

"Thanks." He looked at paper then looked again. "There's been a mistake."

The teller double-checked his screen. "Not according to this, sir. Would you

like to speak to the manager?"

"Please."

Seated in the visitor's chair in the manager's office he read through the

printout of deposits in his saving's account, trying to understand why and how

this could happen. Seventy-six million, four hundred and fifty-nine thousand,

three hundred and twenty-two dollars and eighteen cents.

Bruce, obviously but what the hell was he thinking, dumping this kind of money

into a savings account? And why the hell…?

"Mr. Grayson, is there anything I could help you with or clarify?"

"No, thank you."

Twenty minutes later he walked into Bruce's office, interrupting his weekly

meeting with Lucius. He put the account printout on the desk. "Care to explain?"

"I was going to tell you this weekend; you're twenty-one now, it's your

inheritance from your parents."

"…Yeah, right."

"Lucius?"

"Your parents left you nine thousand dollars after the liquidation of their

estate and I combined that with the seventy-five hundred dollars held in trust

for you from your own earnings in the circus. Bruce asked me to look after it

for you."

"You parlayed sixteen thousand dollars into seventy-six million? Lucius…"

"Lucius is very good at his job, you know that."

"And what am I supposed to do with this?"

"Whatever you want, though I'd suggest that you move it to a larger interest

bearing account than just savings. I'm sure Lucius can give you make some

suggestions."

"…Did you add anything to the initial amount?"

"I added the legal tax free gift limit each year, ten thousand dollars times

thirteen years. That's all."

"So I'd never have to work?"

"So you'd never have to worry. I know you'll always work. If that's all, Lucius

and I haven't finished with our meeting."

He left, pausing to nod at Lucius in thanks.

So that was it. He'd never have to work another day in his life if that was his

decision. He could go anywhere, do anything. Walking through the underground

parking garage towards his bike he became angrier and angrier. How dare Bruce do

this—how could even he have the gall to not tell him that he'd been quietly

salting away tens of millions of dollars as a cushion `just I case'? How could

he have kept this secret since he was eight years old? Didn't he trust him

enough not to blow the money, not to talk about it, not to throw it back in his

face?

And, more than anything else, where did he come off adding to his parent's

legacy, implying that it wasn't enough, that what his parents had saved and

sweated for was inadequate? That was what burned—if Lucius could parlay a

hundred and forty-odd thousand dollars into over seventy million, he could have

done just fine with the almost fifteen thousand that were his own and his

family's money into a perfectly nice nest egg.

Riding up the thruway he thought back on all the times he'd mentally compared

Wayne Manor to his parent's old trailer and, while the manor was obviously along

sight better appointed, the cramped trailer was, and wold always be his

childhood home. The idea that anyone would suggest that it wasn't enough, wasn't

good enough—no. Screw that.

He pulled into the fifteen-car garage, turned off the engine and…stopped,

sitting on the bike, listening to both the silence and his thoughts.

He'd come here with no plan other than to—to what? To rant because he was now

richer than his dreams? Complain that someone cared enough to arrange for him to

be provided for life?

He was being ridiculous.

He pulled his helmet off, glad to be free of the weight and not caring that his

hair was mashed down and sweaty.

In the kitchen he touched Alfred's arm before he could unwrap whatever meat he

was about to prepare for diner. "C'mon, I'm taking you out for dinner."

"A pleasant surprise, might I ask the occasion?"

"—I had a little windfall today."

"Did you, indeed?"

"You wouldn't happen to know anything about it, would you?"

"And would it matter?…I knew that you'd be angry but I trust you have the sense

to know that all anyone in this house—or for that matter, the people in your

life before you came to us—have ever wanted for you is the best, whatever means

may be employed to ensure that."

"And no one thought I had a right to know what was being planned and prepared?"

"Again, would it have mattered, made any difference? I think not and so there

was nothing to be gained, as you surely realize." He got his familiar bowler,

the new one he'd been given for Christmas. "Shall we?"

He didn't say anything, knowing there would be no point. Later, as they drove

home he quietly asked, "Are there any more secrets I don't know about?"

"A silly question, young man; there are always more secrets in this house, as

you well know."

"I don't suppose you'd be willing to tell me about any of them."

"When the time is right. Until then, my best advice is to be satisfied with the

great deal you have."

That was it, there would be no further explanations, he could accept it or not

but it was done. Lucius had taken the money is parents had left him, taken the

money Bruce had gifted him with over the years and grown it beyond all reason,

ending up with more money than he could likely ever spend. The yearly income

along would generate a minimum of three million dollars before taxes. Every

year, if he didn't spend the principal, the money would just keep piling up,

growing. Bruce was right, Lucius was very good at his job.

So, what to do with it? Buy himself a house, cars, expensive toys, trips? He had

all of that and they had never mattered to him, anyway. No.

Charity? Of course. Good causes? Sure. He needed to sit down, probably with

Lucius since he knew what he'd done better than anyone, and make some decisions,

set some goals, make plans.

Tomorrow, he'd think about all of this tomorrow or maybe next week. Lying in

bed, all this went through his mind and beneath it all, under the surprise, the

astounding generosity, the freedom almost unlimited money gives you he realized

that he was till angry. It may not have been completely rational, but there it

was; he'd been lied to through omission. Bruce, Alfred, Lucius, not one of them

had said a word in over a decade, not one word.

He understood it, of course he understood it but that didn't change the fact

that he felt betrayed, patronized, condescended to and treated like a child.

His whole life he'd been upbeat, an optimist, happy-go-lucky, known for his

jokes and light-hearted approach to everything and he still was, but…

He'd take the money and he'd use it but he wouldn't forget about this.

*Coogan Law information credited to the Screen Actor's Guild website.

5/23/09